Uncovering the Assyrian Genocide: Tragedy and Resilience

7th August marks a day of remembrance for the Assyrian community. Known as ‘Martyrs Day,’ the Assyrian community commemorates Assyrian Christians who lost their lives during the Ottoman Empire’s persecution, resulting in the Assyrian genocide, and consequently the Semele Massacre. This commemoration was established by the Assyrian Universal Alliance in 1970 and continues to this day. (1) This article delves further into other atrocities that have hampered the Assyrian community throughout history. It must be noted that this article will only briefly outline the atrocities, and the factors associated to them.

Although the atrocities that will be covered range from the Late Middle Ages to the modern contemporary setting, it is plausible to note that the earliest systematic atrocities of the Assyrians started during the reign of Shāpūr II (r. 309-379 AD) of the Sāsānian Empire of Persia, who initiated the persecution of Assyrians due to perceiving views of political suspicion and sympathizers with their Christian brethren. These views only further exasperated after the Roman Emperor Theodosius I the Great, by way of the Nicene Creed, proclaimed Christianity as the official state religion. The atrocities that followed magnified immensely leading to widespread executions with churches being destroyed, clergy being imprisoned, acts of brutal torture, and forced apostasy. It is ascertained that upwards of 16,000 were martyred during the reign of Shāpūr II. (2) (3) (4)

Tamerlane

Tamerlane led a ruthless campaign at the end of the 14th century against the Church of the East (erroneously labelled “Nestorian”). This furious campaign aimed at destroying this once world-renowned church resulted in its complete collapse in Central Asia, Persia, and China. Untold numbers of Assyrians were killed or enslaved. By 1400, the vast domains of the Church of the East ceased to exist. Assyrian missionary activities after these abhorrent massacres never recovered. The Assyrians and the church as an entity faded away from history. (5)

The late historian Hirmis Aboona writes: After 1295 the Church of the East gradually dwindled into a shadow of its glorious past. Its sharp decline could be seen by the beginning of the fifteen century, when it was unable to call a church council to elect a new patriarch because it had only one metropolitan serving a few communities in their original homeland who had survived the catastrophic events, especially the slaughters of Timur Lang. (6)

Pictured: The monument to the Turco-Mongol conqueror Amir Timur in Shahrisabz, Uzbekistan.

Badr Khan Bey and Nur Allah Bey

Badr Khan Bey, Amir of Bohtan, combined with other Kurdish forces led by Nur Allah Beg, Amir of Hakkari, attacked the Assyrians; intending to burn, kill, destroy, and, if possible, exterminate the Assyrians race from the Hakkâri Mountains (mod. South-Eastern Türkiye).

Spurned by the ideals of Assyrian independence, between 1843 and 1846 the Assyrians in Hakkari were subjected to extensive massacres by Kurdish clans supported by the Ottoman Empire. An indiscriminate massacre took place. Woman were brought before the Amir and murdered in cold blood with those trying to escape were chased down and brutally killed. The number of slaughtered is estimated to have been at least ten thousand. (7)

The London Times newspaper dated 6 September 1843 succinctly captures the wanted savagery of the perpetrators:

The houses of the wretched inhabitants were fired, and they themselves hunted down like wild beasts and exterminated. Neither sex nor age met with favour or mercy; the mother, brothers, and sisters of the patriarch were the objects of peculiar barbarity, the former being literally sawed in two, and the latter most shockingly mangled and mutilated. (8)

The Hamadian Massacre

With the constant threat of state violence regularly espoused with the goals of either to convert, eliminate, or mitigate the local Christian population due to territorial losses in the Balkans (due to Russian intervention) coupled with the notion of Armenian nationalism, an indiscriminate attack was carried out in what initially started as an attack on Armenians in the Diyarbekir vilayet (mod. South-Eastern Türkiye), instigated by Ottoman politicians and religious figures, soon became a general anti-Christian pogrom, targeting both Greeks and Assyrians. (9) (10) The Massacre of Amid was part of the much more massive pogrom known as the Hamidian Massacres (1894–96), which together witnessed the murder of upwards of 200,000 Armenians (11), 100,000 Greeks, and 25,000 Assyrians. (12) To understand the scale of the wholesale attack, French Gustave Meyrier dispatched the following on 9 February and 18 December 1895, respectively:

The state of affairs affects all Christians regardless of race, be they Armenian, Chaldean, Syrian [orthodox,] or Greek. It is the result of religious hatred.

They kicked the doors, looted everything, and if the people were home, they slit their throats. They killed everyone they could find, men, woman, and children, the girls were kidnapped. (13)

Seyfo

From 1914 - 1925, the Ottoman State and its successor, the Turkish Republic, led a state-sponsored genocide aimed at wiping out its Christian population. Amplified by the call to jihad (holy war) by Ottoman religious leader, Sheikh-ul-Islam, against the “unbeliever.” The call to jihad was broadcasted throughout the Ottoman Empire including neighbouring Persia. (14) Augmented by Kurdish tribes, this gruesome and extensive extermination affected the entire Assyrian population across the Ottoman Empire and Persia. Many children and young woman were taken as slaves, entire villages were torched, churches were torn down, and wells were poisoned. Church clergy along with intellectuals were primarily targeted due to the systematic nature enacted; Religious figures such as Patriarch Mar Benyamin Shimun XXI, Archbishop Toma Audo, and intellectuals as Ashoor S. Yoosuf were assassinated. (15) Many also died due to famine and diseases due to long treks by abandoning their homes in the Hakkari region, making their way to join their brethren in Urmia (Iran), and escaping from Urmia to the Baqubah refugee camp (Figure 1) in Iraq.

To this day not enough is emphasized on the psychological effect it had on survivors and the consequences on many generations after. It is estimated that 250,000 - 400,000 Assyrians were killed, estimating at almost half of the Assyrian population were affected. (16)

Jean Naayem in his 'Les Assyro-Chaldeans ET les Armenians Massacares Par les Turcs', Paris 1920, writes:

"[I will] relate the details of the tragic martyrdom of the Assyro-Chaldeans from the Jezireh district on the Tigris [not far] from Midyat, where more than fifty villages whose names I know, villages for the most part fertile and flourishing…were completely sacked and ruined while the entire population was put to the sword." (17)

Seyfo is the name Assyrians use for the genocide. It is an Assyrian (Aramaic) word meaning sword, as the year 1915 was "the year of the sword" for the Assyrians.

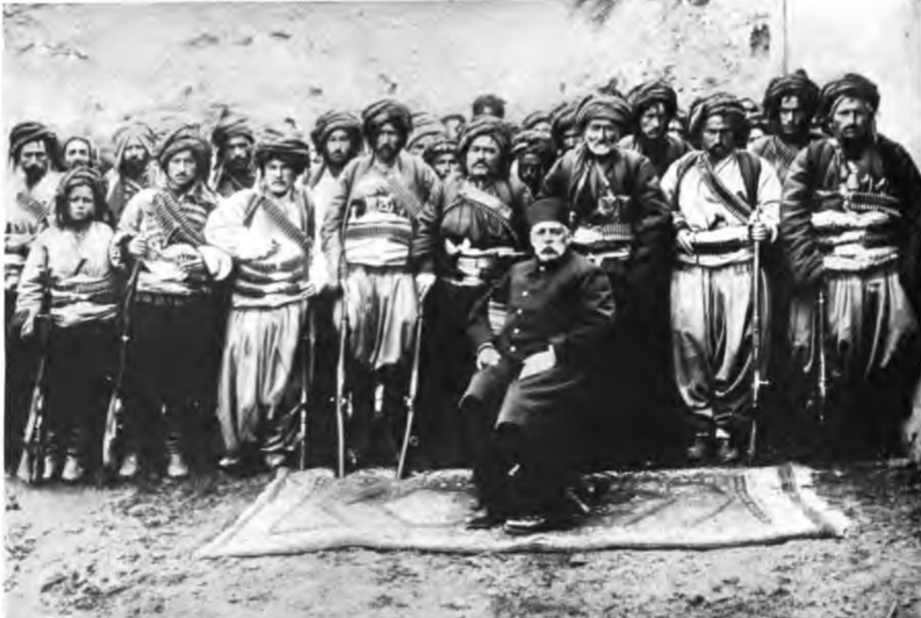

Pictured: Assyrian Tribesman in the district of Tergavar in Urumi. Courtesy of Mr. Paul Shimun from Abraham Yohannan' book, 'The Death of a Nation'. Note: The caption in the book is erroneously labelled as ’Kurdish Tribesman in Urumia’.

Pictured: Kurdish Infantry and a Turkish Officer from Abraham Yohannan' book, 'The Death of a Nation'.

Figure 1: Rows of tents housing refugees in camp at Baqubah, on the banks of the River Diyalah. Catalogue ref: CN 5/2/397

Simele

During the 1920s and early 30s anti-Assyrian propaganda, fuelled by a hostile press, had poisoned the atmosphere as they were labelled 'outsiders' and 'tools' of the West. Rising tensions led to the Assyrians being singled out as the enemy of unity in the newly independent Iraq. Coupled with the issue of settlement and negative sentiments and hostilities, under a thousand Assyrians, who had made their intentions clear to the Iraqi Government of relocating, crossed the border into French controlled Syria who were initially promised resettlement on the condition they disarm themselves. Unfortunately, the French authorities pulled back from their promise due to their relationship with Great Britain but were allowed to return to Iraqi unharmed. Upon re-entering Iraq, the Assyrians were fired upon by the awaiting Iraqi army. 14 Assyrians and dozens of Iraqi soldiers were killed. News of the incident spread throughout Iraq and there was rage and hate with reports of mutilated Iraqi soldiers at the hands of the returning Assyrians. This led to daily demonstrations demanding the elimination of the Assyrian community. (18)

The Iraqi army under the command of General Bakr Sidqi led a campaign of systematic genocide which targeted innocent Assyrians in the town of Semele (Figure 2) and surrounding towns and villages. Men were either round and executed or gunned down by machine gun and rifle fire. The woman had their bellies slashed and their wombs ripped out and placed upon their heads for amusement. Girls who were not raped and burnt alive were taken into captivity by the army and never to be seen again. Most children were stabbed to death. It is estimated that 2,000 to 6,000 innocent Assyrians were slaughtered. In the aftermath, no individual was brought to justice and officials declined to act and denied the massacre. There were also parades for the Iraqi army in Baghdad and Mosul which were met by cheers and jubilation. (19)

A testament to their sacrifice and struggle came when Polish Lawyer, Raphael Lemkin, coined the term ‘Genocide’ in which he utilised the massacre at Semele when defining the term which would later be ratified by the United Nations in 1948. (20)

Figure 2: IWM (HU 89458): Aerial view of Batarshah in northern Iraq, an Assyrian village destroyed by Arabs and Kurds during the disturbances of August 1933.

ISIS

In June 2014, the terrorist organisation styling itself as the 'Islamic State' swept through the city of Mosul and captured large swathes of the last Assyrian stronghold in northern Iraq — the Nineveh Plains. Aiming to drive out Iraq’s First Nation peoples, they succeeded due to the direct lack of organisation by the federal and regional authorities. The moral shock, as a result of their nascent and abject barbarism, had competing parallels with the atrocities of Tamerlane many centuries earlier.

The cessation did not end with those ancient-inhabited towns; they proceeded to destroy the remains of ancient cities which had stood the test of time. What they destroyed was portrayed as an act of carrying out their core tenant beliefs and what was not destroyed had been surreptitiously dealt with in global marketplaces. (21)

Tasked with providing security for the Nineveh Plain region – the Peshmerga of the Kurdistan Regional Government (KRG) – abandoned the Assyrians without notifying the local population of the impending ISIS attack. According to an eyewitness account from an Assyrian woman from the town of Bakhdida, the Kurdish Peshmerga disarmed the Christian Assyrians before IS attacked the Assyrians in the Nineveh Plains (Iraq). The attack on the Assyrians took place in August 2014, which caused all Christian Assyrians to flee in panic. The outcome of the assault has led to mass exile of the Assyrians from the city of Mosul and the Nineveh Plain region. (22) This devastating disaster also coincided with the Yazidi community as they suffered the same treatment by those left in charge of protection. Over 400,000 were displaced, 6,000 woman and children enslaved and sexually exploited, and over 5,000 killed. (23) (24)

ISIS also launched an attack against 35 Assyrian villages in the Khabour Region (North-Eastern Syria) where dozens were killed in the attacks, 230 civilians were taken hostage, and thousands were forced to flee their homes. (25) (26)

This attack also had alarming parallels with the massacre of Semele 82 years earlier in which thousands were forced to flee their homes, and yet again forced to flee their homes in the country they settled in towards an uncertain future in the diaspora.

Soriya Massacre

On 16/09/1969, Iraqi forces under the command of Lieutenant Abdul Karim al-Jahayshee launched an attack the Assyrian village of Soriya (sub-district of Bateel, Dohuk) in northern Iraq. Forty-seven were killed, including the village priest. The most aggravating factor for the slaughter was the ongoing battle between the government and Kurdish Peshmerga forces which resulted in a military car being hit with a mine approximately 4 kilometres away from the village.

The brevity of the massacre was recounted by survivor Noah Yonan:

I was ten years old and I fell on the ground. A woman fell over me and her blood covered me. Other children, too, were covered in blood and thought dead. At the same time, the Iraqi Army soldiers in our village began spreading out, shooting into houses and burning the houses… While we were running, wounded people escaping with us died of their gunshot wounds, bleeding to death. We were all running to the village of Bakhlogia, four kilometers away, to hide. We got to Bakhlogia, but the villagers couldn’t give us refuge; it was too dangerous. So, we ran to another Christian village, Avzarook. (27)

Like the Semele massacre, the aftermath yielded no justice to those whose lives were taken, with officials declined to act and denying the massacre which was compounded by praise towards the government forces who carried out the senseless attack.

Reference List

7th of August, Assyrian Martyrs Day. (2025). Atour.com. https://www.atour.com/education/20010806a.html

Aprim, F. A. (2004). Assyrians. Xlibris Corporation.

Barnes, T. D. (1985). Constantine and the Christians of Persia. Journal of Roman Studies, 75, 126–136. doi:10.2307/300656

Sozomen. (1846). Ecclesiastical History.

E A Wallis Budge, Sir. (1928). The Monks of Kûblâi Khân, Emperor of China : or, The history of the life and travels of Rabban Ṣâwmâ, envoy of the Mongol Khâns to the kings of Europe, and Markôs who as Mâr Yahbh-Allâhâ III became Patriarch of the Nestorian Church in Asia. Religious Tract Society.

Hirmis Aboona. (2008). Assyrians, Kurds, and Ottomans : intercommunal relations on the periphery of the Ottoman Empire. Cambria Press.

Yohannan, A. (1916). The Death of a Nation.

MASSACRE OF THE NESTORIAN CHRISTIANS. (2025). Atour.com. https://www.atour.com/history/london-times/20000801b.html

Suny, R. G. (2018). The Hamidian Massacres, 1894-1897: Disinterring a Buried History. Études Arméniennes Contemporaines, 11, 125–134. https://doi.org/10.4000/eac.1847

Joost Jongerden, & Jelle Verheij. (2012). Social Relations in Ottoman Diyarbekir, 1870-1915. Brill.

Matossian, B. D., & Kiernan, B. (2023). The Ottoman Massacres of Armenians, 1894–1896 and 1909. In N. Blackhawk, B. Kiernan, B. Madley, & R. Taylor (Eds.), The Cambridge World History of Genocide (pp. 609–633). chapter, Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Kalimniou, D. (2019, May 19). Acts of Genocide: 100 years since the massacres. NEOS KOSMOS; Neos Kosmos. https://neoskosmos.com/en/2019/05/19/dialogue/opinion/acts-of-genocide/

Warda, W. (2013). Assyrians Beyond the Fall of Nineveh.

Debt of honour. (2018). Inspiring Publishers.

Yoosuf, A. K. (2017). Assyria and the Paris Peace Conference. Lulu.com.

Varak Ketsemanian. (2014, January 8). Remembering the Assyrian Genocide: An Interview with Sabri Atman. The Armenian Weekly. https://armenianweekly.com/2014/01/08/remembering-the-assyrian-genocide-an-interview-with-sabri-atman/

Naayem, J. (1921) Shall This Nation Die?. [New York, Chaldean rescue] [Pdf] Retrieved from the Library of Congress, https://www.loc.gov/item/22015683/.

Ismael, M. (2020). Assyrians and Two World Wars.

Sargon Donabed. (2015). Reforging a Forgotten History. Edinburgh University Press.

The Simele Massacre & the Unsung Hero of the Genocide Convention. (2018, July 27). National Review. https://www.nationalreview.com/2018/07/simele-massacre-1933-assyrian-victims-still-seek-justice/

Frahm, E. (2023). Assyria. Hachette UK.

Assyria TV. (2020, March 9). Eyewitness: Kurdish Peshmerga disarmed the Assyrians before IS attacked the Assyrians in Iraq. YouTube. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=byDpbFwuq3E

Nadia's Initiative. (2024). The Genocide. Nadia’s Initiative. https://www.nadiasinitiative.org/the-genocide

Ochab, D. E. U. (n.d.). Can The Peshmerga Fighters Be Held Liable For Abandoning The Yazidis In Sinjar? Forbes. https://www.forbes.com/sites/ewelinaochab/2017/07/31/can-the-peshmerga-fighters-be-held-liable-for-abandoning-the-yazidis-in-sinjar/

Erasing the Legacy of Khabour: Destruction of Assyrian Cultural Heritage. (n.d.). Assyrian Policy. https://www.assyrianpolicy.org/erasing-the-legacy-of-khabour

Kidnapped family of Caritas Syria worker freed - Caritas. (2016, February 25). Caritas. https://www.caritas.org/2016/02/kidnapped-family-of-caritas-syria-worker-freed/

Sargon Donabed. (2015). Reforging a Forgotten History. Edinburgh University Press.